Latest News

The Snow Family: A home for Snow without Winter

Years of neglect have turned one of the area's oldest homes, the Snow family home in Neosho Falls, into a state of elegant ruin. George Snow earned the moniker "Big Father" for his work as an Indian agent for the region.

Everything can change in a year, one falling of the snow.

You can lose yourself while finding your home, though shrouded in purple and bruise-black thunderclouds, after the passage of hundreds of miles.

You can see something for the first time, despite seeing it a thousand times before.

You can look in the mirror and find a stranger.

I imagine that’s how Maj. George Catlin Snow would feel today were he to gaze upon his beloved “Rockland Home” tucked away in the southeastern corner of Neosho Falls.

—The moment being akin to staring into the eyes of something alien, though nonetheless intensely alive.

It was a place his daughter Florence, in her autobiography “Pictures on my Wall,” described as “a comfortable place for the family to live … comfortable by pioneer standards.”

Florence herself was quite an accomplished writer, both of prose and poetry, and would later entertain such figures as Abraham Lincoln’s son, Todd, at the Snow’s second home across town called “Fair Havens.”

While still young, she’d gleefully tear across the open prairies surrounding the Falls on her little pony “How-How,” whom she’d received as a gift from native people grateful to her father.

In the spirit of such gratitude, I dreamed of George Snow looking upon the faces of indigenous peoples he advocated for while serving as Indian Agent for the region, when he’d earned the nickname “Big Father.”

Osages, Sac and Fox, Seminoles. Each with their own unique practices to navigate, to both respect and inevitably misunderstand.

I dreamed them coming up from their camps three miles south along the banks of the Neosho with its rich, dark waters, to visit with Snow at the house and at the mission built on-site prior to Rockland’s construction.

In “Pictures” she also elaborates on “the curious squaws who came to the house on endless made-up errands.”

“They proffered rather disconcerting jests in regard to [one] ‘Papoose,’ which happened to be myself, while five older children took things in their stride.”

Throughout such exchanges, one imagines the challenges of communication, the frustration and of course the laughter. The kind of humor shared simply through tone and gesture.

Or sometimes, anger. The rage that boils, seething in the face of gross injustice, violence and less-than-veiled sadness.

Quite a few brazen pioneers had been squatting on native lands, or rather on land that before that time had never been remotely conceived of as “belonging” to anyone.

I’ll admit I have trouble understanding such a concept, the notion that the earth itself belongs to any one person, that a geographical plane might be called “yours” or “mine,” merely because one has the requisite papers.

To that end, following a letter he’d received from Osage chief Little Whitehair, Snow wrote the federal government to call for removal of pioneers intruding on native lands and to enforce treaty boundaries.

Anything to stop the violence.

In a letter of his own, Snow wrote: “something must be done for these people at once,” so as to end “the high-handed stealing from them [so] that we may have peace on the border.”

Responding to Snow’s efforts, then-governor of Kansas, Samuel Crawford, not only callously had the order to remove illegally settled whites revoked, he directed that those same pioneers be armed with guns and ammunition.

At the thought, I could almost smell the blood and powder wafting through the air, a metallic scent that hung in one’s mouth and nose.

A drum-beat echoed almost inaudibly in the distance.

SOMEONE had opened the front door of “Rockland” since last I was there, nearly exposing the painted handprints of children that decorate its interior walls — as well as the splintered wood floor, where in places it looks as if it had been struck with a sledgehammer.

The entrance had recently been defaced with bright red graffiti.

An architectural relic nearly as old as Kansas itself (1862), the house had slowly been reduced to an elegant ruin, thanks to purposeful neglect and adolescent boredom.

Only a few decades ago the house had been abandoned, like the mission before it, which Florence described as falling into disuse “when the Indian Reservation law was passed and the old agencies were no more.”

When the people of the wind and plains were banished from their ancestral dreamscape, the place to which they were and remain inexorably bound.

At the reminder of such monstrosity, the trees guarding Rockland began swaying wildly, until they suddenly stopped and seemed to vibrate in the stark evening light.

Perhaps the house’s collapse is a bit of poetic justice, I thought, a kind of delayed revenge for having one’s cultures erased.

For those missions supported by the Bureau of Indian Affairs were often also sites of violence of a different kind, not of blood, but of heart and mind.

They were places of assimilation, where the aim was to “civilize,” to train the people of the wind and plains to live, speak, work and worship like whites.

To transmute a largely free and unbounded population of pantheistic hunters into Christian farmers, as Thomas Jefferson infamously advised.

Difficult to say which violence is worse — though Florence describes her father as “progressive,” so perhaps he should not be subject to such rebuke.

In fact, George Snow even took native people with him on his trips to Washington, D.C., in order to advocate for their interests.

One occasion generated the following humorous anecdote.

Florence writes that one “keen First American had been greatly impressed with a dinner given in their honor, and during his first meal at home he said to his squaw, on finishing his hog and hominy, ‘Take him away!’ Then he called ‘Bring him back!’ repeating the two orders until he could eat no more of the ‘courses’ thus secured.”

That is, the chief was so impressed by the table service he’d received, he decided to request analogous treatment at home.

I doubt the chief’s wife was similarly impressed.

Thus breathing in the now-confused air swirling about Rockland one last time, I turned my eyes skyward, into its flat bright pastels, and walked away.

Sometimes it’s best to leave judgment to the river.

Nikkeltown: The triangulation of Nikkeltown

An old schoolhouse and cemetery in Woodson County mark Nikkeltown, a Mennonite settlement.

As the simplest shape in geometry, triangles are everywhere, the most fundamental of connective structures beyond the line.

In that sense, triangles are also indispensable to thinking, the form through which abstract concepts begin to emerge.

Cattle in a pasture. A pioneer graveyard. A crumbling rural schoolhouse. No three things could be simpler, right?

That is, until you begin to look closely, triangulate, tessellate.

In the pasture at Nikkeltown, the cattle were dirty white and rusty red and black, though not quite like some moonless night.

When first I arrived, they called out, those neopolitan bovines, heralding my presence, but soon their attention was drawn back to nipping the short spring grass.

Nikkeltown was once home to a group of Mennonites, whose German ancestors answered the call of Empress Catherine the Great (1763) when she invited Europeans to transplant to Russia.

The Mennonites thus fled compulsory military service in places like Prussia, and quite a few had come to call Russia home by the mid-nineteenth century.

The respite was only temporary, however, as in post-Catherine Russia, military exemptions expired after 20 years.

So once again, the Mennonites were on the move — this time, to America, and eventually, Kansas.

They steadily crossed the continent, heads hidden, every day praying for survival against sickness, starvation and temptation.

Around 1878, eighteen families landed in Woodson County, thanks to land-deals made with the M.K. & T. (Katy) railroad, and ended up living in a sandstone sheep-barn owned by wealthy Turkey Creek rancher Charles Weide.

Eighteen families in one barn. Now that’s some close living quarters.

As I stood there, in the triangle between cattle field and graveyard and schoolhouse, I could almost hear them murmuring to one another, or reading softly, in a three-fold combination of Dutch, German and Russian — a dialect termed rather unflatteringly as “Flat Dutch” or “Low German.”

“Am Anfang schuf Gott Himmel und Erde … Und Gott sprach: Es werde Licht…”

INTERRUPTING the dream of voices, a small blackbird in the Mennonite cemetery had swooped in to perch atop a tall grave and was tearing mercilessly at a worm, thereby making it a grave for two.

How many millions of times has this happened on earth? Where the burial place of one living thing becomes the occasion for innumerable others.

Perhaps the entire history of life itself might be viewed in relation to death stacked upon death, producing layers.

That too, is how one makes a sod house — by sedimentation.

The German-Russians who’d made their home at Nikkeltown had learned the technique in their home countries, and it’d immigrated with them.

More than 20 “soddies” were constructed, and several continued to stand for generations afterwards.

The work must have been back-breaking: cutting strips from the prairie soil held together with bluestem grass, then one by one, placing them in strategic patterns and layers.

According to one local account: “These houses all had dirt floors, swept clean and hard. Sometimes the walls were plastered with a mixture of mud and straw. After the soddies were built for some time the heavy rains would to a certain extent wash the dirt away from the sod roots, making it necessary at times to cover the outside with the mud mixture.”

I dreamed them, then, in my mind’s eye, Mennonite pioneers working in the blistering, blinding sunlight, some in long sleeves and long dresses, floating about like mud-daubing wasps, filling cracks and joints with trowels and bare hands.

They, too, were making a triangle: gather straw, gather mud, apply to walls. Repeat.

I HAD become distracted when I noticed a sign hanging from the Nikkeltown schoolhouse nearby, but laughed out loud when, rather than reading “District #43,” “built in 1900” or some other relevant bit of information, it simply said in small yellowed letters: “No hunting except by written permission.”

What of hunting for remnants of the original sandstone school building, via written traces left behind by local historians?

What of chasing the ghosts of children calling out from an old school photograph: Willis, Barrett, Klingenburg, Opperman, Neufeld, Tallman.

Does that constitute permission?

The song of meadowlarks burst out against a gusting wind, and each time this collision occurred, I remarked on the openness of the scene surrounding me.

The cattle were low to the ground. Cemetery stones low to the ground. District #43 school house low to the ground. “Low German.” And I, too, was low.

Above, was the stretching, torturous sky, which in Kansas consumes the possibility of conquering either time or space.

In fact, in Kansas, the sky is low as well, and reached to my feet and to the cattle’s hooves and perhaps even below.

Supposedly there are more cattle in Kansas than people, and as I sat between those hungrily tearing at the field, and the graves in what was once called “Nikkle’s Burying Ground,” I began to see their stout bodies in an overwhelmingly shadowy light.

Today, they strut and canter before the glorious Kansas horizon. Tomorrow, they’ll pass through human guts.

At least their lives have been granted the dignity found in a clear and distinct purpose, despite likely never fathoming it themselves.

SOMEHOW I have to find a connection, I kept thinking. Triangulate between cattle and cemetery and schoolhouse.

How is an education like chewing? What is it like to be born to die and be eaten? How is learning like death?

— One takes a concept, perhaps, and ideally, rolls it over again and again, covering it with saliva, until it becomes palpable. Typically, until it fits with what one already believes.

— One comes into the world, and in time, knows that life will end, that no matter how much one struggles and strives, there will come a point at which life is reabsorbed and returned to the earth.

— One is at first one thing. Then there is learning, perhaps. And now that thing no longer exists. For if it ever was learning, truly, then there is no longer the old thing, but a new one.

Triangulation, tessellation, poetic hallucination.

Thoughts melting and sprawling into one another in some blue-black haze, like sticky juice on fingers produced from some of the first Mulberry trees transplanted to Kansas by the Mennonites at Nikkeltown.

Belmont Area: Feeling the icy wind at Belmont

The Belmont area contains some of Woodson County's earliest and most harrowing stories, especially that of Muskogee Chief Opothleyahola and the "Trail of Blood on Ice."

The sky was cloudless, passing from silver at the horizon to soft blue at the apex of the dome of the world.

I was sitting next to the grave of Doyle “Bud” Neimeyer in Belmont Cemetery, near the “new” Yates Center reservoir, watching the small orange and brown butterflies flit about in tiny eccentric circles.

Someone had placed a chipped red brick nearby, seemingly as a gift, that read: Standard Coffeyville Block.

And adorning Neimeyer’s final resting place, a quote from naturalist philosopher Aldo Leopold:

“A Thing is Right when it tends to preserve the integrity, the stability, and the beauty of the biotic community. It is wrong when it tends otherwise.”

It’s an insight of immeasurable depth and caring, one that speaks to an ethics beyond anything white men have yet devised.

An ethics where all touches all, where nothing stands alone. Where nothing survives in isolation and without others.

An ethics wherein everything needs everything.

I only knew “Bud” as a child when I was a Boy Scout, with my pressed navy shirts and yellow patterned scarves, when he showed us such profound sites as the Native American petroglyphs at Dry Creek Cave.

He kneeled in the dirt pointing, and somehow I can still see him there, excitement effervescing out beneath his signature cap.

It can be no accident, then, as to why he is interred here, at what is perhaps the place of greatest historic significance in all Woodson County, at what was once the intersection of wagon trails leading from Humboldt to Eureka, Neosho Falls to Coyville.

X marks the spot.

JUST down Kanza Road at 70th is the Belmont Corner, once home to upwards of 600 pioneers and 20 cabins, a tavern and post office, blacksmith and hotel, and an agency where native women retrieved meagre government rations.

In a letter written by E.T. Wickersham in 1934, he recalled: “the squaws would ride up to the store, tie their ponies and go into the store, and come out with a sack of flour [then] put it on the pony behind the saddle.”

“They were all dressed alike with a small blanket that reached from their shoulders to their knees … So while they were tying the flour to the saddle they had to let go of the blanket in order to use both hands, and the blanket would drop down, exposing their naked bodies to the icy cold wind until they got on their ponies.”

Perhaps unsurprisingly, of all things contained in the letter, it seems the young E.T. was deeply affected by the naked women and girls, but also the indigenous peoples’ haircuts, their methods of child-rearing and their homes made of grass and hides.

IN WOODS south of the cemetery lie the ashen traces of Fort Belmont, a modest militia holdout against the Southern Confederacy.

I often feel as though I can hear the subtle whinny of horses in the little earthen corral there, the shouting of young men foolishly eager to face down Rebs in gray coats and red men in red paint.

In a field to the east, you can yet walk the faint outline of the parade-grounds and ovular track where militiamen would race native people on horseback.

And one sweltering summer day, I couldn’t help but wash my hands in the milita’s little walled up spring hidden along Big Sandy Creek, which somehow remains after almost 160 years.

WIND from the south leapt up and began to tossle the cedar trees that guard the cemetery’s oldest graves, persuading their shadows to tilt.

One twisted branch is shockingly white, and stands out in exile from the rest.

Below, I had chalked the stones belonging to Richard Barritt and his son Everett, and still wore turquoise stains on my fingers from the act.

Their names erupted from being worn to becoming unbearable in their crystalline articulation, standing and nearly screaming out from the white and withered passage of years.

In his day, Barritt lived on the southwestern border of the county, along the Wilson line, though the place there once called “Barritt’s Hill” no longer bears that name in the mind of almost anyone living.

The air had become almost cold, despite the mid-April sun, though I was chilled more from the white-tailed doe that suddenly disrupted the quiet woods at my back.

There, several thousand Muskogee people once sheltered during the Civil War, at a time when few trees stood to keep the fearsome winter at bay.

Despite wanting to remain neutral, they had done battle with Confederates in present-day Oklahoma, and after abandoning supplies were forced to march across the frozen and desolate prairie leaving behind a “trail of blood on the ice.”

According to Wickersham, “they came up here by the thousands, [such that] the woods were full of Indian camps.”

Though promised life-saving provisions by the Union, they found nothing in Kansas but rancid meat and broken promises.

I shivered then, perhaps just as much from the air as the thought of children crying in the snow, their fingers and toes blue and brittle from frostbite.

A little boy raised his dark eyes and stared at me, mercilessly, motionless.

Both his feet had been amputated.

In the face of such horrors, how can the sunlight there do anything but mock the forever-stained ground, profane the scattered plot where countless Muskogee fell?

Where the bones littered the earth …

EVERY time I had the urge to look up while writing, I hesitated in fear, despite having walked those woods a dozen times before, in search of the unmarked grave of Chief Opothleyahola and his daughter, whose name I have not yet learned.

She died in winter 1862 from tuberculosis, whereafter wreaths and garlands adorned the hallowed place her people had laid her.

I desperately want to know it, her name.

I want to speak it aloud, sing it in an aboriginal tongue the syllables of which have never entered nor left my blasphemous mouth.

I want to say it with all the force of time and the Milky Way Galaxy, so that that place might forever bear witness to The Impossible.

I want a black hole to unfold in those woods and swallow the light forever.

Today, a visitor to Belmont Cemetery can be stunned to wordless reflection by the seemingly unmarked nothing of it all, and perhaps that silence is the only appropriate response.

For what else is one to do before the knowledge of such suffering but cover one’s mouth like Job?

Let the birds sing instead. Let their high whistles and warbles invert the horror that hangs on.

Or rather howl instead, howl from a place of darkest mourning.

Goings Cemetery: The Fire of Randolph Goings

The story of a former slave's challenges contrasts against the burned prairie at a cemetery site.

I stood transfixed behind the barbed-wire fence by the side of the gravel road, watching in awe as bright orange fire snaked across the pasture in Liberty Township.

The air was heavy with dancing smoke that turned the air a hazy blue and obscured my view into the distance where a single tree with gnarled black branches stood.

An April wind suddenly began to churn in the southwest, such that what had been a controlled burn began to surge hungrily in my direction.

Flames leapt more than a dozen feet into the air and soon the soot was swirling frantically all around me.

A monstrous roar sounded, an insane popping and crackling of dry brush mixing with an atmosphere pulsing and bursting with movement.

In “Prairyerth,” William Least-Heat Moon described a similar scene as “red-gold on jet, angles and curves, oghams and cursives of flames, infernal combustings.”

Despite feeling intense heat on my face, at first I was immobilized, shocked still as “the red buffalo” began to stampede near the fence-line.

Realizing almost too late there was no fireguard burned along the roadside, fight turned to flight as I spun around to race for the open car-door.

As I sped away, I watched through the rear-view mirror as flames gnashed at the roadway where I had stood only moments before.

The 25 million year-old indigenous ritual of cleansing and inoculating the prairie had almost purified me as well.

Realizing what parallel I had found myself on, I proceeded slowly down the gravel road to the east, gazing into the distance at columns of smoke rising in almost every direction.

During the spring burn, rural Kansas looks like a war-zone, a volcanic blast site.

At that moment, an ambulance tore by, lights flashing red and blue, and I wondered who else had gotten a little too close to the flames for comfort.

SLOWING to a stop as I came to the northerly bend in the road, I could see white crosses adorning the field in Goings Cemetery, marking out a fraction of the 50 people interred there.

At one time you could have also seen a number of raised sandstone vaults that had once been a unique feature of the pioneer burial-place — situated along the LeRoy-Eureka trail — where long smooth stones had been quarried and dressed nearby, then fitted together with iron bars.

The vaults are all gone now, having been mostly shattered along with the names they bore like those of Sarah Pickering and her daughter, who along with several other wagon-caravan travelers perished from some lethal disease such as cholera, tuberculosis or smallpox.

People used to place animal bones around the sarcophagi as a prank, in order to scare the living daylights out of small children or friends.

More recently, someone claimed their cracked remnants were resting in a barn nearby, so as not to be further damaged.

Inside the gate, you could see how a burn had been allowed to tear through the graveyard, scorching most of the field but leaving the sunken grassy halos around the graves untouched.

Amid the ashen “prairie coal” contrasted several bright green ovals adorned with tiny yellow dandelions, and it was possible to see just how many bodies occupied the now-unmarked plots.

Though long dead and dessicated themselves, as the cemetery’s only two trees keep close company with the deceased, they were spared the cleansing burn as well. This last summer, they were filled with enormous bumblebees.

Oddly enough, in “A Sand County Almanac,” Aldo Leopold notes how most trees in the midwest are only as old as the first white settlements (and cemeteries) here — dating to the mid 1800s — precisely because widespread farming led to the cessation of most prairie wildfires that had until then prevented them from growing.

If you don’t believe him, he dares you to count the rings.

Fires have certainly been part of shaping the landscape of Goings Cemetery; for when I last visited it was as if the mouth of Hell had been invited to open and paint a chilling image there of an afterlife spent in perdition.

Not that the cemetery’s namesake, Randolph Goings (1840-1871), needed any additional reminders, as it seems his own life was already hellish enough.

He and his first wife Lucy Jane were born slaves near Charlottesville in Albermarle County, Virginia — ironically, the same birthplace as county namesake and life-long advocate for slavery, journalist and territorial secretary, Daniel Woodson.

I therefore view Woodson and Goings as foils or inverses to one another, though it’s doubtful the two men ever met.

Before coming to Kansas by way of Ohio, Goings and his family first had to secure their Free Papers, which listed them as “mulattos.”

For whatever reason, in Ohio he became estranged from his first wife and six children, which likely had something to do with meeting a woman by the name of Mary K.

As Mary was white and Randolph was multi-ethnic, you can imagine it caused quite a stir, especially since they had to stop along their path to Kansas in Illinois so that Mary could give birth to a son named Thomas.

In 1858, Goings and his new family settled along the big bend in Turkey Creek, atop a rocky knoll east of the cemetery, where water is typically shallow and the undergrowth so thick and wiry you can barely traverse it.

A few decades ago, paleontologists from Emporia State University found what they believed to be dinosaur tracks along the creek bed, and though I’ve yet to see them, the rancher who lives nearby swears they exist.

During their time at the cabin near the creek, four more children were born to Randolph and Mary, including Sarah and Mary Etta, who although they evaded a permanent stay in the little burial place covered in fire and dandelions, eventually faced some serious travails of their own.

As records are spotty, it seems the only battle we know of Randolph facing for sure after the horrors of Virginia slavery were to battle with Woodson County commissioners in Neosho Falls over the placement of a road near his home. (He won.)

However, as one of the only black or brown pioneers in the county at the time when the Bleeding Kansas conflict was determining whether or not slavery would be legal there, it doesn’t take stretching the imagination much to figure Randolph and his white wife led incredibly difficult lives.

Let’s be honest: given the lingering specter of such racism, their relationship would be derided and condemned by many in southeast Kansas even today.

After Goings died in 1871 when he was only 31 years old, and Mary K. shortly after, at only ages six and four, the little girls Sarah and Mary Etta became the wards of pioneer neighbor Asa Whitney, a figure who casts a rather long shadow across the county’s early history.

Whitney was a commissioner who had a school named after him, which still stands today though it’s been used as a shed for cattle supplies for years now. But he was also accused of serious crimes by Sarah Goings while she was a teenager, both against herself and her father’s property.

What Whitney was indicted for, we may never know, but he was nonetheless acquitted.

But the trouble didn’t end there. When Randolph’s first wife got wind that he’d died, she too tried to seize his land-holdings and property from Sarah and Mary Etta. (The girls lost.)

It’s a complex family drama that, though fragmentary, reveals how the emotional and legal difficulties of life do not belong merely to our own time.

Thus when you stand in the seemingly tranquil little cemetery that bears the Goings family name, and is Randolph’s final resting place, it’s impossible not to feel the sadness and the anger born of their daily struggle to survive.

A calm spring wind may sing from Turkey Creek across the naked plains, but if one is attentive, you can still feel the fire of Randolph Goings.

Historic Woodson Co. Jail: Get the torches and pitchforks

A visit to Yates Center's old jail coincides with a retelling of a 1915 bank robbery.

A snowy sky hung dimly over the Yates Center square as I pressed my face against the glass of what was once the State Exchange Bank.

I imagined the teller counter had returned, the bars, the safe and two unassuming young men entering the door in February 1915.

Unmasked and well-dressed, they strolled to the desk around lunchtime and asked whether a “Mr. Hines” had been in.

Before the cashier W.J. O’Donnell could answer, though, he found a .33 caliber revolver staring him in the face.

“Throw yer hands up and hold ‘em high,” growled one of the genteel fellows, as the other scrambled up and crawled through the opening of the teller window.

In four minutes flat, over $4,000 in cash had been liquidated, and in a flash, the thieves were out the door.

I imagined them bursting past me through the exit, causing me to reel backward toward the “painless” dentist office that once stood next door.

No sooner had they gone, but I seemed to hear the muted sound of poor O’Donnell yelling at the top of his lungs from inside the locked vault.

The ghost of a woman named Blanche Winters pressed inside the building, and with keys in hand, managed to free the flabbergasted prisoner.

Soon the hunt was on.

Everyone in town had been beset by a lolling panic, with Model-Ts and rumors tearing about in every direction.

Who were these demonous outsiders who’d dared intrude upon our placid villa? And what terrible disease of sloth and violence had they brought with them?

This is OUR TOWN!!

Get the torches and pitchforks …

JUST in the nick of time, ol’ “Bill” Reedy screeched to a halt in front of the bank, then raced inside to inform Sheriff Carrol he’d spotted the thieves making a break for it on the edge of town.

To reenact the scene, I leapt into my car like the Sheriff and his posse, racing east as closely as possible along the rail trail as if voraciously hunting the license plate of some out-of-town flapper.

I was sure I could see the faint outline of their tracks as I approached.

And sure enough, there they were, the two miscreants shivering in the bushes near a sycamore with faces pale as milk.

The Sheriff had his gun leveled, and O’Donnell was sneering, “Young man, hold your hands just as high as you made me hold mine.”

Instinctively my arms shot into the air!

With this, multiple heavy bags of cash heavily thudded to the ground, setting bills blowing in the wind.

Realizing that they couldn’t actually see me, I left the deputies to their duties and crept slowly back through Yates Center to find the townsfolk scurrying everywhere like venomous ants.

Hundreds of shotguns and rifles, hammers and knives were being brandished in rage.

Peoples’ blood was up, and red filled their eyes. Not a good time to be passing through.

Little did they realize the targets of their fearsome ire were already in custody, safety confined and unable to further contaminate the unsoiled air of the little town’s purity.

DAYS passed, and Harry Milton and James Harmon were on the verge of losing their minds.

They paced back and forth within the steel walls of the sandstone jail, anxious and angry.

How long had they been there?

Marks scratched on the wall said three weeks.

But three weeks had begun to feel like three millenia, especially without whiskey and cigarettes — not to mention the endless hollow tolling of the Baptist Church bells nearby.

Milton, whose real name was Jesse Billings, had no intention of staying put; and when the moment arose, he took it.

Using the stray piece of metal he’d filed to a knife-point, he threatened another prisoner to help them escape the interior cage, then he and “Jimmy” wriggled through a hole in the ceiling.

Despite someone spotting them make a run for it nearby, past the original courthouse (from Defiance) and collection of businesses once called “Smoky Row,” soon they were home-free.

Frigid wind whipped at their thin uniforms, turning their skin cracked and blue as they again hobbled down the railroad tracks, but they had made it.

That is, until they were arrested two months later and banished to the state pen at Lansing.

Milton got 21 years. The max. Baby-faced Harmon, a slap on the wrist.

BENEATH the massive catalpa tree that hangs over the old stone jail — which hides behind the northeast corner of the Yates Center square — I stared in awe at how the two men had managed to escape.

The structure seemed impenetrable, like the shadowy darkness inside.

And after gaining access to the jail’s interior, I was even more impressed: not only by the heavy bars and unbreakable latches, but by the endless rambling graffiti still visible on the walls.

One etching is of a pig’s backside, with curly tail and pointed ears. Another, a human figure with tiny phallus. And name after name after name.

One is the cage’s manufacturer: “Pauly Jail Bldg & Mf’C Co, St. Louis, MO.” Dealers of Hell on Earth.

Though condemned as unfit for human habitation in 1963, the jail continued to operate for another four years.

MORE recently, I’ve been rereading “Walden” and “Civil Disobedience” by Henry David Thoreau, which led me to imagining him there behind similar bars, imprisoned for refusing to pay his taxes.

Not wanting his money to be wasted on supporting the brutality of slavery or the imperialist conquest of the Mexican-American War, he was condemned to rot.

At least until an anonymous benefactor, perhaps Ralph Waldo Emerson, bailed him out.

Despite the brevity of his stay, the experience led him to conclude that “[u]nder a government which imprisons any unjustly, the true place for a just man is also in prison.”

Yet how many have the courage to disobey in such fashion, thereby requiring us to rethink our attitudes towards those we find incarcerated?

And how do we not conflate those who disregard the law due to a childish refusal of orders (given for the common good), with those who draw attention to injustices being done to others?

The saints and revolutionaries of the world are too often grossly misunderstood.

Yet the torches and pitchforks await them just the same.

Piqua: Piqua from dusk till dawn

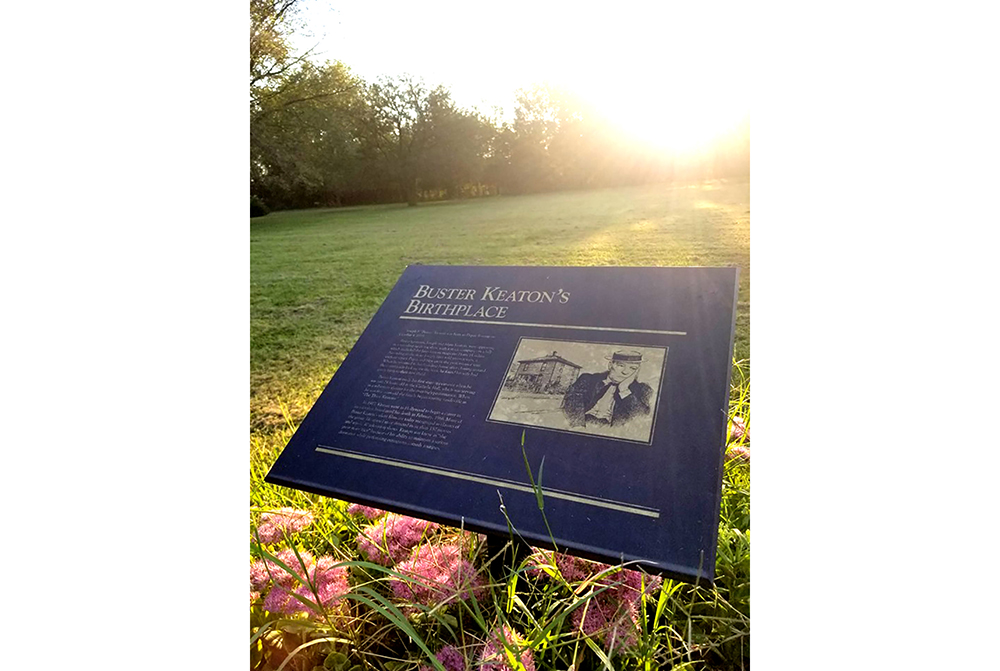

Piqua's history includes being the birthplace of silent film legend Buster Keaton. Its history is visible all over town — if you look closely enough.

DAY THREE — I was sitting near the birthplace of silent film legend Buster Keaton in Piqua when Gov. Laura Kelly’s state-wide “stay at home order” came through.

The COVID-19 pandemic sweeping the nation for the past few weeks had finally hit home.

In 1886, smallpox broke out in Piqua, whereupon the town was quarantined for six weeks.

Guards were stationed on all roads leading into town. Travelers were told to drive their wagons and carriages on through Piqua without stopping.

Adults were only allowed to leave home for trade. Children were forbidden to leave their yards.

Dr. J.L. Jones, the public health officer from Neosho Falls, set up a tent on the west side of town where he cared for the sick.

Many endured the virus and were left with scars. A young man by the name of Bert McKinsey didn’t survive.

Looking southeast toward the site of the railway junction that breathed Piqua into being — April Fool’s Day, 1882 — I imagined the train cars passing while the roads were patrolled by sentries.

The thought made me shiver, like the nearby purple clover trembling in the angry wind.

Earlier that morning I had felt a rush of excitement when I discovered the rectory from the original St. Martin’s Catholic Church was still standing and had been converted into a house.

That feeling, though, quickly transmuted into dread and a sense of foreboding.

I tried to distract myself by looking for remnants of the Piqua State Bank and department store belonging to Markus and Niemann, with its well out front. Folk said the water used to taste and smell like rotten eggs.

Old-timers claimed you could chew on it, but it was probably still preferable to eating June bugs. I only mention it as a bacchanalian by the name of Heckman used to do so for a lark outside the Knights of Columbus Hall.

Granted, drinking sulfurous water and consuming insects are probably preferable to the bitterness tasted by those who lost their fortunes when the bank collapsed in the Great Depression.

Given the crushing economic impact of COVID-19 so far, though, it may be that this is another disastrous past that’s repeating itself.

Not that Piqua will necessarily notice, as financial hardships long ago turned the little town into a somber study in absence.

DAY TWO — Late afternoon, the robins, doves and meadowlarks were singing in the still-bare hedge trees surrounding Old St. Martin’s cemetery west of Piqua.

The first thing everybody notices is how the graves of the 97 adults and 64 children are segregated, so that upon rising the sun first touches the Irish-German youth.

Folks used to call it the “Budde Place,” despite Bernard Budde not having lived (there) long enough to ever officially own it.

His 4-year-old son, Bernard Henry, drowned in a nearby creek, the place where he had told his father that he often spoke with angels.

I was sitting beneath the impressive concrete crucifix at the cemetery’s middle, in view of Bernard senior’s and junior’s graves, where it seems the number of people buried here ended up being fewer than planned.

I scooped up a piece of the cross that was at my back and examined it. There’s a large chunk missing near the top of the sculpture that seems somehow appropriate, imperfect, like the intrusion of humanness and embodiment into the dream of Wholeness.

It reminded me of when, in “Pilgrim at Tinker Creek,” Annie Dillard speaks of “the uncertainty of vision, the horror of the fixed, the dissolution of the present, the intricacy of beauty, the pressure of fecundity, the elusiveness of the free, and the flawed nature of perfection.”

For a cracked and broken perfectness was there: in the moth flitting in the grass at my feet, where I was once again surprised by the noise of this supposedly “sleepy” place: the low roar of cars on the highway, the rumble of muddy farm trucks along the gravel road.

The cedar tree in front of me had almost begun to conceal the sun’s glare, and wore its luminosity like a halo.

Perhaps heaven is glimpsed in these suspended moments when we feel love or awe in silence, reflectively, knowing it must end but believing it will come again.

Or perhaps heaven comes in a croon of notes from a meadowlark’s beak, complex and interweaving — the softly spoken spell of a ghost who tarries along with us through the disorienting trail of life.

One of the German graves there speaks of being held in the arms of peacefulness, a solace that in its ambiguity might refer either to God or Death.

DAY ONE — The frogs were chirping after the rain when I stopped the car in Piqua.

A cloud of blackbirds had burst overhead toward the northeast, and the air was just cool enough to suggest that spring had not yet conquered winter.

From here, between the defunct post office and foundation of Neimann’s store, I could see the place where silent film legend Buster Keaton was born, and where in later years he visited with his wife, Eleanor.

I wondered what he would have thought of the yellowed museum dedicated to his work that hides inside the Rural Water Station.

He’d likely say it’s important to keep a straight face so that the audience projects its own reaction onto the actor.

Unable to conceal its own response, a dormant catalpa tree near Silverado’s bar and grill reached up between the power lines on all sides as if in an act of rebellion.

FOR whatever reason, it inspired me to investigate the depot around the corner, repurposed to serve as a storage shed for the Grain Co./CO-OP.

I kept having the urge to look inside, though I’m sure it’s just an empty shell. But it is a husk with memory, and that is what matters. One must simply be still to know.

It’s odd, however, that in Piqua, no matter how meditative you try to be, you can nevertheless hear the roar of traffic on U.S. 54, and I’m reminded of how the first schoolhouse ever built here — Bramlette No. #27 — was so close to the train tracks that it had to be moved.

Sounds carry here throughout this living monument, like the cries of coyotes whose eruptions suddenly pierced the coming dusk.

Their wails tore violently at the air, echoed through the streets and then vanished.

I wondered if at one time, when it still retained its occupants, they’d have been as excited about the derelict chicken coop up north as I had been.

As the sun set, wrapped in cobalt, I was (again) reminded of Dillard, who spoke of being “cradled in the swaddling band of darkness. [Where] even the simple darkness of night whispers suggestions to the mind.”

Vernon’s Alexander Hamilton: The time aliens stole my cow

More than a century ago, notorious Woodson County prankster Alexander Hamilton claimed UFO-flying aliens stole his livestock. The legend soon took on a life of its own.

Just when you think things can’t get any weirder, that’s when the aliens arrive.

Or at least that’s what an old settler named Alexander Hamilton claimed happened at his ranch south of Vernon in 1897.

He staked his sacred honor on it.

Apparently the extraterrestrials stole and dismantled his prize heifer, which perhaps explains why even today the cattle at Hamilton’s pasture seemed jumpy.

Everywhere you go in Woodson County, black Angus walk right up to the fence, looking for food. Here they appeared skittish, darting away as soon as I approached the barbed-wire.

The entire herd repeatedly stampeded off as if they’d seen a ghost.

Their owner, too, was wary, and demanded to know why I was parked by his pasture, carefully observing his charges.

ACCORDING to the Yates Center Farmer’s Advocate, on the night of the abduction Hamilton claimed he and his family had been awakened by panicked cries.

Assuming it was merely his mischievous bulldog, Hamiliton went to the porch to scold him when he saw it: an enormous “airship descending over [the] cow lot about 50 rods from the house.”

He swore the craft was 300 feet long, dark reddish in color and cigar-shaped.

Hamilton and his son, along with other farm-workers, snatched up axes and sprinted toward the ship with its shining glass panels.

It was then they saw “six of the strangest beings [they’d] ever seen,” communicating in a manner none of them could understand.

As the farmers approached, the aliens shined their lights on the men, then quickly accelerated the craft upward.

As the ship ascended, it trailed a cable of sorts to the ground where it had snared an unsuspecting heifer, who balled and cried furiously as she was pulled from the earth below.

Too late, Hamiliton and his men watched in horror as the craft — with heifer in tow — shot into the night sky, then vanished into the northwestern stars.

SHELTERED in my own craft, I stared long and hard into that same cloudless northern sky.

After the cattle got used to me, they decided it was safe to come and take a look. They nibbled at the field greedily, yellowed fragments flying away in the wind whenever one would raise their head.

You could hear their mouths working as they ate, a kind of snuffling, sniffing, scarfing, as they tore tender greens from the earth.

One particular lady, her furry face caked with mud, came right up to the fence, then immediately turned her backside. Her tottering calf stood beside her, watching, too young yet to have a yellow tag punched in her ear like her mother’s.

Another suckled greedily from his mom’s udder, and both had become visibly agitated from the exchange.

In the distance, I could hear the creaking groan of an oil well pulling up and down.

Suddenly the train approached from the south, its blasting alarm audible in the distance.

I imagined its arrival was like that of Hamilton’s alien visitors: an enormous hulk of metal distorting the air as it moved, signals flashing.

Just south of the crossing I watched as the lights alternated red-blank, blank-red, akin to the airship’s colorful displays.

DING-DING-DING-DING-DING-DING. The right-of-way’s warning was as frantic as Hamilton and his men.

The ground began to rumble as graffiti-covered Union Pacific cars thundered by, and some of the cattle lowed in response.

Hamilton himself claimed to have been traumatized by the encounter, unable to sleep for decades to come.

“I went home that night,” he said. “But every time I would drop off to sleep I would see that cursed thing with its big lights and hideous creatures. I don’t know if they were devils or angels or what, but we all saw them and my whole family saw the ship and I don’t want any more to do with them.”

Perhaps this mostly had to do with what happened to his cow.

The morning following the close encounter, Hamilton ran into a neighbor, Lank Thomas from Coffey County.

Thomas had found the mutilated body of Hamilton’s cow.

Thomas also claimed there were no tracks of any kind, such as those of a carnivore who could have been blamed for the violence.

IN ORDER to assuage the skeptics, Hamilton obtained the signatures of local political figures and others with high reputations to testify to the veracity of his claims.

Such personages included the sheriff, district attorney, postmaster, multiple pharmacists and the register of deeds.

Because Hamilton was known as someone with a morbid sense of humor, as well as a prankster and spinner of tall tales, most folks around the area knew the story to be a hoax.

Soon, however, large U.S. and British newspapers — including the St. Louis Globe-Dispatch — began to reprint the tale and it became an international phenomenon.

Today a quick fact-check reveals that in spring 1897, tales of Unidentified Flying Objects were sweeping the globe. Hamilton’s may have been the first to include the theme of cattle mutilation.

At the time, however, some folks were taking the legend as seriously as any other claim made in the papers, unable to discern between a fantastic or “yellow journalism” narrative made for the sake of entertainment and those designed to inform.

Ironically, making such a discernment is still our task today as citizens of a digital world, as we're compelled to sift through mountains of disinformation in order to locate the truth.

To refuse this task is in turn to forsake ourselves.

Trials of the Daniel family: The cabin on Big Sandy

A Yates Center treasure holds tales of hardship. The Daniel family cabin has been rebuilt along U.S. 54 in Yates Center.

The cold rain was falling in hard green drops as I rounded the forested corner that hides Big Sandy cemetery.

Cedar trees dripped in the morning mist, and hungry blackbirds were calling near the rectangular sandstone gate.

As I approached the entrance I paused, listening, straining not only to hear but to feel something of the place, confident that its ghosts would reappear.

Indeed, anyone who’s ever visited this place claims it’s haunted.

Ignoring the weather, I shuffled through the wet grass toward the rear of the cemetery plot, intent on visiting some old friends.

And there they were: more than a dozen unmarked pioneer graves with peculiar shapes that when taken together look like rows of teeth lining an open mouth.

The light was almost absent despite it being mid-morning, and the entire space was cloaked in purple shadows.

Unable to resist, I reached out my hand and ran it along the meticulously chipped sandstone surfaces of more than one stone, wishing the gesture would yield up a story from the soft earth below.

I stood for a moment at each one, waiting, smelling the air as it wafted from the nearby creek, which this summer had been exploding with dark red algae blooms.

At first, the only answer was the windy spray of precipitation across my face.

Eventually, though, someone called my attention as he is often wont to do: Josiah Daniel, 1828-1879.

Both he and his father’s family lived in these dark woods once brimming with wild mean hogs and lean black turkeys, to the south of the cemetery, surrounded with hundreds of indigenous people for neighbors.

They lived in an expansive log cabin, the diminished version of which now sits at the Woodson County Historical Museum in Yates Center along Highway 54.

The reconstruction combines pieces of the old Daniel place with the chimney from another cabin belonging to a pioneer named David Askren, and if you know its story you’ll never look at it the same way again.

WHERE others see a quaint and cichy little structure, imagining a warm hearth and “the sweet old face” of Mrs. Eliza Daniel as she pivots in her rocking chair, one can just as easily view a mute witness to epidemic illness and gross injustice.

In short, to hardship and death.

Summer 1864, while Josiah’s father was farming the Big Sandy valley, smallpox broke out among the native tribes who were living there, transmitted to them by whites.

In time, many in the Daniel family were afflicted by the red plague as well.

As a boy, Josiah recalled seeing the Osage and Muskogee people suffer untold horrors: their arms and faces covered in oozing sores, many becoming sick and blind and broken.

The Muskogee had been chased up from Oklahoma by Confederates two years earlier, and led by Chief Opothleyahola, had already endured the monstrous ordeal known as the “Trail of Blood on Ice,” a flight into Kansas rife with starvation, frostbite and broken promises.

Josiah’s mind was especially seared with the sight of what are sometimes called Native American “burial trees,” where a resting place for the dead is suspended in the air atop a biar supported by tall wooden poles.

According to certain tribes’ customs, these poles would be painted red or black, as were still-standing trees used for a similar purpose.

People would be wrapped tightly in blankets with their belongings, Josiah said, and placed where others might visit the deceased and speak with them.

While walking the forests along Big Sandy, especially when nearing a high hill or overlook, I nightmarishly dream that I can see them too.

THEY are buried all around me, I realized — these silent victims of a disease that claimed 300 million people in the 20th century, despite being eradicated by 1980.

As the revelation shuddered through my mind, I could almost feel the ground tremble with sadness and anger.

For a moment, it seemed that even the birds stopped singing.

It was then Josiah reminded me of another story, a trauma so etched on his brain that when interviewed years later, it remained at the forefront of his recollections.

Near the Daniel home once stood another seemingly innocent structure: a log schoolhouse where local children laughed and learned and played.

But when Josiah’s family was living nearby, a group of vigilantes tried three men in that schoolhouse for stealing cattle, despite most folks knowing the accused were really only guilty of having learned too much of the vigilantes’ own misdeeds.

After a sham trial lasting nearly three weeks, the accused were condemned to death and sentenced to hang in trees just north of the Daniels’ own home.

On that terrible eve, two of the men were brought into the cabin for their last meal, a tale not easily forgotten when entering the space today.

Standing in the woods, the rain began to abate, and I thought about the cabin’s seemingly cozy interior, how the table with its walnut furniture made in Humboldt looks set to welcome and embrace guests.

… Who are about to face lynching.

They eat slowly, methodically, savoring every particle as only those who are about to die can endure, as the hands of the antique grandfather clock grind inevitably forward.

Then those men swung back and forth just as slowly from the trees along Big Sandy.

Josiah said two were oak trees, one was a blackjack.

Fall of that year, the schoolhouse was moved.

I stood there in the cemetery, gazing into the treetops, watching as the cedars shifted in the once-delayed dawn.

The sun was rising high enough in the east that its sickly white light had begun to pierce the scene, as I focused on the branches as they ached and expanded, casting off the weight of water.

At my feet lay the dead, from pestilence and lies and time, murmuring as they too eagerly shifted to embrace the yellow star’s unceasing lack of judgment.

Fegan and the CCC: Trouble on Lake Fegan

A Woodson County lake's unique features are many, from its ornate sandstone pillars to the monuments to the workers who helped build it. Yet the imposing elements give a foreboding of trouble, even to those simply interested in sight-seeing.

No matter how many times I ford the low-water crossing near Lake Fegan dam, I hold my breath.

Doesn’t matter the water is only two inches deep, though it gurgles and babbles as it rolls over the concrete slab of road.

Perhaps that’s why I stopped just before the aforementioned spot on the pretense of snapping photos of the dam’s ornate sandstone pillars.

I was clicking away, looking for angles, when I saw someone approaching in the distance, who just happened to be the now-former Sheriff of Woodson County in a gunmetal gray truck.

Wayne Faulker was once a member of the Kansas Highway Patrol, and from his silver-gray buzzcut, looks like a military man as well — somewhat reminiscent of the infamous drill sergeant from the film “Full Metal Jacket.”

“Trouble?” he asked.

As William Least-Heat Moon points out in “Prairyerth,” it’s a familiar refrain to the outdoor writer-explorer, code for “Are YOU trouble?”

He mentioned my Virginia license plate, but didn’t seem to care much, especially after I mentioned my name, who I’m related to, and who he knows, along with rattling off a few historical details about the lake.

“This place was named after Ben Fegan, who owned this land in the ’30s.”

After awhile you get used to the test questions.

Striking up a conversation, Faulker seemed proud of the fact that he took presidential candidate Bob Dole on a 16-county tour of Kansas, though slightly miffed when I mention Dole’s adversary, former U.S. President Bill Clinton.

Faulker recalled being impressed by the courthouse at Cottonwood Falls in Chase County while on his tour with Dole, though doesn’t bite when I suggest the work of the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) that built Fegan in the 1930s — one of FDR’s “New Deal” programs — is a shining example of how large-scale government programs can be successful.

AFTERWARD, I was sitting just north of the dam at a decaying picnic table, trying to decide whether or not it felt comfortable out: one minute the cool breeze was pleasant, invigorating, but when it stopped and everything held breathlessly still, it became stifling.

That Sunday morning, the complexion of the water matched that of the sky, an almost identical blue separated by a band of pearl horizon and the olive-green of innumerable post oaks.

It hardly seemed possible the lake had been recently drained now that its waters had returned, which is a testament to how historical and environmental changes can occur suddenly yet seem as though “things were always this way.”

When it comes to places like Lake Fegan and its cobalt water turned to waves in the breeze, such relatively sudden transformation is benign; when one considers the “disappearance” of people and places due to atrocities, such haste is chilling.

“Trouble?”

Though I’d wanted to dwell upon dwelling there, pay close attention to the brown bell-shaped leaves that had begun to fall, I thought instead about the native peoples once living nearby along Sandy Creek, how they caught smallpox from whites and died in the thousands.

Many white settlers died, too.

None would have known a site called Lake Fegan as it did not exist yet, but would have known the place by other names.

Is it possible to open oneself to those sacred labels, dream them turning in the wind?

I MYSELF am still trying to discover what it is I’m endeavoring to open up by resettling here, what exactly it is for which I am on the hunt.

Despite having assembled detailed written and photographic maps of the county, I feel more lost than ever — like a blackjack leaf adrift atop the water.

An enormous raven’s black wings then sliced the sky, and once again I was reminded of the impending nature of death, how it circles us, slowly, gliding and swooping, breathing us in, trying to sense whether the moment is right.

In this, death is in league with the Great Mysterious: a partner, confidant or secret lover.

“Trouble?”

Walking to the water’s edge for a moment, I was reminded of my younger brother, how he haunts South Owl Lake, the “old” Yates Center Reservoir, for hours on end, fishing for crappie in an attempt to hold his mind in some sort of meditative equilibrium.

Being there, writing at Lake Fegan, I continued to search for mine.

The wind rattled through the oaks again, tousled the Johnson grass, toppled and redirected the tiny blue and yellow forest butterflies, yet did not inflate my lungs.

My breath was shallow, heart heavy and thoughts dark, despite the tranquil morning and the soothing song of crickets.

On June 15, 1933, the Toronto Republican reported, “The streets here were the scene of some celebration this noon when the word came through that all was well, and rightly there should have been for this project is a big one and one that has been worked for very hard by local men and sportsmen.”

Reading such sentiments about the lake is hard, as they exude a jovial mood which on that morning seemed completely alien, a stranger.

I had listened for the birds but heard only the whispers of trees.

Another article from 1933 mentions how between 12 and 15 thousand people visited Fegan on its opening weekend, and says “some mighty big fish stories” were told to accompany general “praise by fishermen” for the site.

Almost 90 years later, devoid of human activity, one could call Fegan a ghost-lake, where one can only imagine the cacophony of CCC building camps or the sparkling shouts of children.

Today Fegan stands as both a monument to a grander rural past even as it perhaps points to a more promising future — though it’s hard to imagine people today enthusiastically inviting in thousands of outsiders from regional building partners in Allen, Wilson, Neosho, Greenwood and Coffey Counties as was done in the 1930s.

“Trouble?”

When the wind gusted, an invigorating chill shot through me and I longed for it not to end.

To feel completely alive in this and other places, absorb their energy, undergo a resurrection of the spirit in some a-religious way, perhaps it is this for which I hunt.

I do not desire consuming the blood and marrow of some specific life, such as a bison or whitetailed deer or bobcat, but the tissue of life itself.

I long to quench myself on life’s own vital fluids, its sinews, build a home of its bones and clothes of its skin.

If only I can open myself to the strange glory I sense is on the cusp of penetrating me, perhaps then I might recognize this as my native sky and know I am finally home.

Buffalo Bill in Yates Center: Tending the Hotel Woodson

Yates Center's Hotel Woodson has been a part of the community for more than century. Among its guests in the days of yesteryear was Buffalo Bill Cody.

YATES CENTER — The wind was blowing steadily from the south, and my breathing shallow, as I sat catty-corner from the Hotel Woodson on Yates Center’s town square, watching the vehicles pass.

My favorite are the golf carts, which folks around here use as a kind of inverse convertible. Instead of the top being down, it’s the only thing that’s up.

I asked my friend, four-branch veteran and unapologetic Kansas Democrat, Troy Shaffer, if he chose to live in the hotel given its incredible past, but said his decision was based on cheap rent as opposed to nostalgia.

After some pestering, Troy gave me a tour of the hotel, where he confirmed the tin ballroom ceiling and sleek wooden bar are indeed original, though the floor plan has been converted from twenty-one small rooms into four large ones.

In a letter written by Edwin Guy Reid, son of the hotel’s original owner, he recalls having to swap every stained-by-who-knows-what sheet, shove coal in all 12 stoves, fill all the oil lamps and burn endless piles of garbage.

He also added: “in the morning you would have to … [e]mpty all the slop jars and carry all the waste water down back of the hotel and dump it.”

You can imagine poor Ed trying his best not to gag as he repeatedly descended the stairs before reaching the hog pen.

In his nasal drawl Troy pointed north, remarking “Now, all the outdoor toilets and everything was back there, too. And the well. There was a big well. It was 1887! You still had to have water. There was prolly a dresser and a water pitcher in each room, you know, to warsh up in.”

No amount of water, though, I imagine, was enough to fully exorcise the ghostly residues of countless ragged prospectors and cattlemen, belaced prostitutes and cigar-smoking oil barons.

ABOVE THE hotel’s cream-colored corbels and Victorian era moulding, the sky was a single shade of periwinkle.

Its monochromatic expanse was oceanic, as if one could turn the world upside down, the air would possess a solidity that would allow one to reside within it, be held in the arms of that vastness and receive something ineffable and uncannily still.

It dawned on me just how many sandstone blocks there are lining the hotel’s facade, but I didn’t have the patience to calculate them.

When next we see one another let me know what number you came up with, as I’ve yet to find consensus among counters.

Don’t worry. We have ample time for such things in this place where the clock hands crawl, present and past bleed into one another and divisions between culture and history break down.

One feels this most acutely, I think, at night — when the streetlights gleam eerily and the wraiths of Yates Center begin to murmur aloud.

A SQUIRREL scolded me from the tree behind my back, despite my having arrived first.

A passing golf cart then compelled me to analyze the brick streets paved in the early years of the twentieth century, particularly the intricate weave at the corner of Butler and State Streets.

Frank Butler was a confidant of town namesake Abner Yates, and instrumental in the campaign to make Yates Center county seat. Despite the town eventually taking his own name, Yates had wanted to name it “Butler.”

My attention directed at Butler Street, I was reminded of when Troy told me he was born on the Yates Center square.

“A block off of it, yeah,” he explained. “It’s straight down there. Dr. [Harry] West delivered a lot of babies in this town!”

Looking south down the street to where Troy had pointed, my sight first turned to the intricate sandstone arches of what was once T.L. Reid’s “Livery, Feed and Sale Stables.”

A flier for the shop advertises renting a team and buggy for weddings, picnics and funerals.

People used to comb the manes of horses there in front of the tall, three-door entryway. Now they cut human hair one building down at Hairbenders Salon.

When acts like Buffalo Bill’s Wild West came to town, according to Edwin Reid, “A couple cabs from the livery stable were rented, and the horses decorated with banners and plumes, as they would parade around town advertising a show.”

Bill Cody himself caused quite a ruckus, it seems, “filling up with booze and getting pretty noisy.”

He and his crew were tossing back whiskey like water and pinching grapes, shooting the juice at one another, when a waitress named Daisy Obanjon slipped in the mess they were making.

Dishes leapt and crashed to the floor, porcelain shattering into shards. The hotel manager, Edwin’s Canadian-born father Thomas, then confronted Bill and got squirted in the eye with grape-juice for his trouble.

Irate, he seized Bill by his long wavy hair and yanked him from his seat. T.L. would eventually become sheriff of Woodson County and feared neither man, god nor legend.

“Believe me you never saw such a fight,” wrote Edwin. “They wrecked the dining room office and mother ran out in front of the hotel with an old dinner bell and started ringing it. … Show people had a hard time putting up at the hotel after that.”

THE SKY’S soft blue had become pierced by jet-black vultures. They circled the immense white water tower to the north, reminding me of the smaller rust-colored tower that fell into disuse during my lifetime.

Perhaps I’ll have to scale the water tower at some point, get a prey-bird’s view of things, dream when the entire hotel block was an orchard.

That’s what this sojourn home is about: seeing, regarding familiar things for the first time.

Take for example the trees shading the northwest corner of the square. They’re elms, but I realized I knew nothing about them.

Turns out they’re deciduous, meaning they shed their leaves in fall, covering the streets in waves of yellow, red and gold.

They are also hermaphrodites, “male” and “female” simultaneously, spreading their genes by pollen loosed on the wind.

At the dawn of their appearance 40 million years ago, these trees were evolving in Asia. Hence like so many people and things in Woodson County, the elms on Yates Center’s square are the children of immigrants.

Now they’re everywhere, leading one to forget the time when Yates Center was nothing more than a vast sheep pasture covered with acres of bluestem grass.

As Troy exclaimed, recounting when he’d once flown over town in an airplane: “To see Yates Center from the air, it’s just totally different from up there. My god, I thought that it was more open than that! It’s gotta lotta trees in it now compared to open prairie like it was!”

I noticed the wind had stilled again, American flag by the Legion outpost motionless.

Something in the way it held the light drew awareness to the warm shadows cast nearby.

The French writer Marcel Proust taught readers to observe the smallest, seemingly insignificant details in everything — and in striving for such attentiveness to the world, what is accomplished?

Indigenous people and Christians alike have both regarded life here in southeast Kansas as the Great Mysterious or God’s Mystery, and perhaps that’s what we’re aiming at.

To peer into the enigma of the everyday, engaged in a process of becoming curious about all that surrounds and bends within ourselves.

Waterways: The majesty of Owl Creek

A bouquet of sights and sounds fills the scenery around Owl Creek. From owls and crows to chiggers and fish, wildlife is a constant companion.

Moments after arriving at one of Owl Creek’s southerly bridges, I heard them: HOO-HOO, HOO-WHAAA! WHAA!

For once I’d arrived in time to witness the sunset, though obscured behind drooping trees along the riverbank, leaves brightened with yellow in the evening light.

I saw the sky reflected in dark pools below, more “green-gray bark waters” like those of the Verdigris River on Woodson County’s western edge.

A murder of crows adorned the scene, chiming in with the low roar of the baler and other haying equipment I passed down the road.

If you follow the creek southeast, you’ll eventually arrive near Humboldt, a trajectory roughly followed by many early residents who had “in-town” business.

And if you follow the creek northwest you can find the ruins of Durand and its depot, as well as South Owl Lake, better known as Yates Center’s “old” reservoir.

WHEN I SET OUT for somewhere to write in this area, what first came to mind were cemeteries: Pioneer graves like that of Emily Condict, who died in a carriage runaway accident, Owl Creek Lutheran and Catholic, or Linder-Orth, resting places of German immigrants and their descendants.

But then it dawned on me: Owl Creek is named for something very much alive, and its ghosts could wait.

Though one senses them everywhere.

I tried to imagine indigenous people especially, enter the dreamtime with eyes open, and saw them gathering water, fishing, and camping on the open prairie long before it was farmland.

I heard their songs commingling with those of the cicadas, the smoke from their fires blending with the golden-blue light.

WHOAAAA!!! the owl close to my left exclaimed. Do not forget about me! I, too, am part of this immortal choir!

Though I couldn’t see its face, I dreamed it square and brown, with piercing yellow eyes and sharp black beak.

She knows something about dreaming as well, this early-risen nightbird.

More than once I heard a fish break the water with a plop and a splash.

Often it was aggressive, with wiggling bodies breaking hard against the muddy surface, echoing out rings of movement.

The wind was almost still, the temperature reminiscent of fall.

My breath, too, was without depth. I sat, waiting, chest barely rising and falling, like a snapping turtle resting on the creek-bottom, waiting to snare an unsuspecting passerby.

The welts on my leg throbbed from exploring woods surrounding the ruins of Fort Belmont, when my friend Luke Heller and I were swarmed by hornets.

My right ankle was inflamed with chigger bites as well, what seemed like a thousand little red marks where microscopic arachnids borrowed my skin.

Sometimes lately I feel like what a chigger must: crawling across vast surfaces of the county, searching for nourishment and warmth, trying to dig in, looking for something to sustain a ceaseless hunger.

Someone then tore by in a large green truck. I waved, but didn’t get so much of a nod. A reasonable response, I suppose, to someone perched atop a bridge in a bright red lawn chair.

After becoming anxious in my not-belonging, I turned to leave and came face-to-face with an enormous male raccoon on the bridge.

He trundled along, back arched, not noticing me at first, then beat a hasty retreat.

A hard flapping I’d been hearing also gained its source, as a silver heron charted horizontally, leap-flying from tree to tree.

It battered thousands of feathers with each wingbeat, an impossibly dense sound, until I realized it was accompanied by a mate. Then a third, a fourth, a fifth heron.

They disappeared upstream, angling toward the position of the setting sun.

Old Man Coyote, that legendary sly fellow, next erupted : Ow-Ow-Owww! Then another: Owwww!!!! Then what seemed like a dozen: Eiiiiieeww!! Owwiieeoouuu!!

Then silent.

I walked back toward the car and noticed two white-tailed deer crossing the gravel road far ahead. Their coats reddish-orange as they crossed the soybean field north of the creek.

This place is so full of life, I thought.

Yet just as I began to philosophize, a woodpecker hammered against a nearby tree, the hollow knock interrupting thought and demanding it instead become observation.

THOUGH IT’S POSSIBLE these words will fail and disintegrate, I want to convey to you the sublimity of the Kansas sunset that filled the horizon north of that bridge and beanfield.

The treetops were black, with intricate outlines that, were I a red-tailed hawk or some other being whose religion is the sky, I might have been able to relate their nuance.

How do I convey the awe felt while facing the horizon’s aurora that night, its blue-green curves falling toward the earth, the hazy pink wisps and orange hues that lined those shadowy treetops?

How do I explain that out there, amid the fading colors of evening, the red-oranges and turquoise, the oceanic space carved out, hollowed and refilled — in that moment, beyond hope, I found a reason to keep living?

When I knew everything would be okay, even if it isn’t.

Because the sky is broad and the sun will set tomorrow until it doesn’t, when you or I are no longer here to see it.

When the creatures of Owl Creek are the only ones with eyes left to see.

But until then, I invite you to weep there, before that hallowed sunset, if only a single tear — there where the colors dim and turn and bleed, and the night blesses you as it comes.

Life does not make sense.

It never will.

But there on the edge of coming stars, in that place open to the cosmos, where arms of the Milky Way christen the darkness and make it holy beyond all human thoughts and words …

You will see Venus rise in the southwest, accompanying a rainbow that pervades the entire sky and overcomes the boundaries between darkness and day.

Abandoned dreams: The silent monument of Silver City

A unique mining operation was once the site of a pioneer gold rush.

Gazing across the expanse of the open-pit mine at Micro-Lite LLC just north of the Woodson-Wilson line, at first all I saw was sand, immeasurable tons of it.

I then had to pause as an immense yellow bulldozer, dirty with grit, rumbled by. I watched in subtle awe, unable to hear my thoughts, as the enormous scoop pivoted, dropping dusty material into a nearby grate.

“So what is it that you want, exactly?” the mine’s foreman had groaned in exasperation, clearly annoyed by the eccentric curiosity-seeker who’d ask to check out the area. Though after a fumbling attempt to explain myself while feigning curiosity about gadgets in the control room, he eventually gave in.

He even half-admitted that he knew why I was there, saying “Yeah, whenever we see something sparkle, we take a look.”

“Do I need a hard hat?” I asked.

“Ugh, I’m sure you’ll be fine,” he grumbled, then hastily jogged away toward a nearby building.

As I depart the mine’s processing area with its enormous rock tumblers turning incessantly, I recall that 90 million years ago during the Cretaceous Period a volcano began forming beneath this place. And as the nearby machines shook the earth, perhaps I gained some minute sense of that force.

Back in a dinosaur-inhabited world, molten rock bled its way up from a hundred miles below the earth’s crust, spreading like tree branches through fractures in the sediment, collecting in such great volumes as to cause the formation of dome-like hills throughout this area between Buffalo and the little village of Rose.

After noise from the heavy machinery and dozer finally thundered only in the distance and I was able to regain my focus, I noticed something glimmering nearby. I bent down and lifted a chunk of brownish-red material, then crumbled it in my hands.

When the sun’s light reflected just right, I saw it again. Those bronze-colored flakes that look as if a penny had been shredded and dispersed through the rock. The mineral is called peridotite or lamprolite, the residue of magma having cooled and hardened.

This igneous formation is one of the rarest and strangest substances on the planet.

The only other known lamprolite deposit in Kansas, the Rose Dome intrusion, is located just a few miles to the northeast.

In other places where deposits like these exist, such as the Kimberly region in western Australia, diamonds have been found. Murfreesboro, Arkansas, is one such place, home to Crater of Diamonds State Park, where tourists pay a few dollars to try their hand at prospecting for a day.

At Murfreesboro in 1990, a woman named Shirley Strawn found the world-famous Strawn-Wagner Diamond, a colorless, internally flawless stone valued at almost $35,000.

The undiscovered wealth lurking beneath Woodson County may be immeasurable, a seemingly wild supposition, though one geologists from Emporia State University even support.

It was a belief shared by prospectors in the late 1870s, who swarmed the area in droves when it seemed they’d discovered a paradise rich in gold, silver, precious metals and stones, recalling the fervor of the California Gold Rush and sites like Deadwood, South Dakota.

The sandstone that’s morphed into blueish-purple quartzite, which litters the mine floor and dyes the soil an inky hue, must have captured their imaginations as well.

As one countian, Eva Cox Depew, put it at the time: “Rumors of this newest El Dorado had spread like wildfire and daily through Yates Center by covered wagon, horseback and afoot, battered old prospectors shared the road with young fellows heeding the call of adventure for the first time.”

“No need to speculate on the destination of a man with a few possessions wrapped in a bandana and tied to the end of a stick carried over his shoulder,” she wrote in a letter a hundred years back.

Indeed, even though I knew better, I felt an uncontrollable giddiness as I scanned across the wall of the mine, where my own shifting movement seemingly caused the entire world to glint.

Every few feet as I traced a slow path around the mine’s rugged outline, I had to stop and touch a new surface, photograph another formation, break off another jagged fragment of amethyst or some other crystal.

Despite no town or even a post office having ever manifested, it became absolutely clear how this place earned its nickname, Silver City.

Yet it is a name shrouded in scandal, one spit with a curse from the tobacco-encrusted mouths of those who once uttered it. Around 1878-1879, poor farmers and naive investors threw away untold fortunes in the area in order to invest in mining operations with names like “Yellowjacket.”

Seems those poor fellows were the ones to get stung, though.

As I stood atop the hill overlooking the mine-pit, just south of where the tents and shanties stood so long ago, I could almost sense the ferocious ghosts of the place, the frustration and despair felt when it was eventually discovered there was no silver, no gold, no words of comfort to be uttered for those who had thrown away their livelihoods.